Tracing our journey to count and compute from our fingers to supercomputers.

Introduction: Tracing Our Journey to Count and Compute from Our Fingers to Supercomputers

The history of calculation is a fascinating journey through human ingenuity, tracing our species’ efforts to count, compute, and understand the mathematical relationships that govern our world. From the earliest use of fingers and tally marks to the sophisticated algorithms running on modern supercomputers, the evolution of computational tools reflects both our growing mathematical understanding and our need to solve increasingly complex problems.

This journey spans thousands of years and encompasses cultures from every continent. Each advancement in computational technology has built upon previous discoveries, sometimes gradually and sometimes through revolutionary breakthroughs. The story is not just about tools and machines but about the human minds that conceived them and the societies that adopted them.

The earliest forms of calculation were intimately connected to the human body. Counting on fingers and toes was natural and universal, leading to number systems based on fives, tens, and twenties. The word “digit” itself comes from the Latin word for finger, reflecting this intimate connection between our anatomy and our numerical concepts.

As societies grew more complex, so did their computational needs. Trade required accurate accounting, astronomy demanded precise calculations, and engineering projects necessitated sophisticated mathematical techniques. These practical demands drove the development of more powerful computational tools and methods.

The transition from physical counting aids to abstract symbolic representation was a crucial milestone. Early number systems used concrete objects or marks to represent quantities, but the development of positional notation and abstract symbols allowed for more complex calculations and the expression of mathematical relationships.

The invention of mechanical calculation devices represented another major leap forward. From the abacus to the mechanical calculators of the 17th century, these devices allowed for faster and more accurate computation, freeing human calculators to focus on higher-level mathematical reasoning.

The 20th century brought electronic computation, which fundamentally changed the nature of calculation. Computers could perform calculations at speeds unimaginable with mechanical devices, opening up new possibilities for mathematical modeling, scientific research, and technological innovation.

Today, we live in an age of ubiquitous computation, where algorithms process vast amounts of data in real-time, enabling everything from internet search to artificial intelligence. The journey from simple counting to algorithmic processing represents one of humanity’s greatest intellectual achievements.

Understanding this history helps us appreciate both the continuity and the revolutionary changes in computational methods. While the tools have changed dramatically, the fundamental human desire to count, calculate, and understand mathematical relationships remains constant. This continuity provides a framework for understanding current developments in computing and anticipating future advances.

The story of calculation also reveals the social and cultural dimensions of mathematical development. Computational tools were not developed in isolation but emerged from specific historical contexts and served particular social needs. The adoption of new computational methods often required changes in education, business practices, and social organization.

Finally, the history of calculation demonstrates the cumulative nature of human knowledge. Each generation built upon the achievements of previous ones, sometimes improving existing methods and sometimes making revolutionary breakthroughs that changed the fundamental nature of computation. This cumulative process continues today, with modern computational methods building on centuries of mathematical and technological development.

Ancient Tools: The Abacus and Early Number Systems

The abacus stands as one of humanity’s earliest and most enduring computational tools, with versions appearing in virtually every ancient civilization that developed sophisticated mathematics. This simple yet powerful device, consisting of beads or stones moved along rods or in grooves, enabled merchants, scholars, and administrators to perform arithmetic operations efficiently for thousands of years. The abacus represents a crucial transition from purely mental calculation to external computational aids.

The earliest abaci were simple counting boards, consisting of a flat surface with grooves or lines where counters (stones, beans, or shells) could be moved to represent numbers. These devices appeared in Mesopotamia around 2700-2300 BCE, where they were used alongside cuneiform numerals for commercial and administrative calculations. The Sumerians and Babylonians developed sophisticated positional number systems that worked well with counting board abaci.

The Roman abacus, used throughout the Roman Empire, employed a bi-quinary coded decimal system. Each column represented a decimal place, with beads in the lower part of the column representing units (one through four) and beads in the upper part representing fives. This system made addition and subtraction straightforward and allowed for efficient representation of Roman numerals.

In Asia, particularly in China and Japan, the abacus evolved into more sophisticated forms. The Chinese suanpan, developed during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368 CE), featured seven beads per rod—two in the upper deck (heaven beads) and five in the lower deck (earth beads). This design allowed for calculations in both decimal and hexadecimal systems, reflecting the Chinese use of the hexadecimal system in weights and measures.

The Japanese soroban, derived from the Chinese suanpan, was simplified to one heaven bead and four earth beads per rod, optimized for decimal calculations. The soroban became so efficient that skilled operators could perform calculations as quickly as early electronic calculators. Japanese schools taught soroban techniques well into the 20th century, and the device is still used today in some traditional settings.

Beyond the abacus, ancient civilizations developed various other computational aids. The Inca quipu, a system of knotted strings, served as both a recording device and a computational tool. Different types of knots and their positions on strings of various colors represented numerical and categorical information, allowing for complex record-keeping and calculation.

Early number systems reflected the computational needs and cultural preferences of their societies. The Egyptian hieroglyphic number system was additive, with symbols for powers of ten that were combined to represent larger numbers. The Roman numeral system, still familiar today, also used an additive principle with subtractive notation for certain combinations (like IV for four).

The Babylonian sexagesimal (base-60) system was particularly sophisticated, allowing for easy division by many factors (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 15, 20, 30). This system influenced our modern timekeeping (60 seconds in a minute, 60 minutes in an hour) and angular measurement (360 degrees in a circle). The Babylonians used this system with their counting boards to perform complex astronomical calculations.

The Greek alphabetic numeral system assigned numerical values to letters of the alphabet, allowing for compact representation of numbers. This system was used with counting boards and influenced later developments in European mathematics. Greek mathematicians also developed geometric methods for solving algebraic problems, reflecting their preference for visual and spatial reasoning.

In Mesoamerica, the Maya civilization developed a vigesimal (base-20) number system with a concept of zero, represented by a shell-like symbol. Their calendar calculations required sophisticated arithmetic, and they used a dot-and-bar notation that was well-suited for their computational needs. The Maya zero was one of the earliest positional uses of zero in the Americas.

The efficiency of abacus-based calculation was remarkable. Skilled abacus operators could perform addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division rapidly and accurately. The tactile and visual nature of the abacus engaged multiple senses, making it easier to track calculations and detect errors. This multi-sensory approach to computation was one reason for the abacus’s enduring popularity.

The abacus also facilitated the development of computational algorithms. The systematic movements of beads according to specific rules represented early forms of algorithmic thinking. These procedures were passed down through generations of merchants and scholars, forming a body of computational knowledge that was refined over centuries.

The transition from ancient computational tools to more modern methods was gradual and varied by region. While the abacus remained popular in Asia, European mathematicians began developing symbolic algebraic methods during the Renaissance. However, the abacus continued to be used alongside these new methods, demonstrating its practical effectiveness.

The legacy of ancient computational tools extends to modern times. The principles underlying abacus operation—positional notation, systematic procedures, and external memory aids—remain fundamental to computational methods. Understanding these early tools provides insight into the cognitive processes involved in calculation and the evolution of mathematical thinking.

The Birth of Algebra: Al-Khwarizmi and the Power of Systematic Problem-Solving

The birth of algebra as a distinct branch of mathematics is traditionally attributed to the 9th-century Persian mathematician Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, whose work revolutionized mathematical problem-solving by introducing systematic methods for solving equations. The word “algebra” itself derives from the Arabic term “al-jabr,” meaning “reunion of broken parts,” which appeared in the title of al-Khwarizmi’s seminal work “The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing.”

Al-Khwarizmi lived and worked in Baghdad during the Islamic Golden Age, a period of remarkable intellectual and cultural flourishing. The House of Wisdom, where he was employed, served as a major center of learning where scholars from different cultures and traditions collaborated to translate and expand upon the mathematical and scientific knowledge of earlier civilizations. This environment of intellectual exchange was crucial for the development of algebra as a synthesis of Greek geometric methods and Indian arithmetic techniques.

Before al-Khwarizmi, mathematical problem-solving was largely geometric, following the traditions of ancient Greek mathematics. Problems were solved through geometric constructions and proofs, which, while rigorous, were often cumbersome for practical applications. Al-Khwarizmi’s innovation was to develop symbolic methods that could solve problems more directly and systematically.

In “The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing,” al-Khwarizmi classified and solved linear and quadratic equations using two fundamental operations: al-jabr (completion or restoration) and al-muqabala (balancing or reduction). Al-jabr involved moving negative terms from one side of an equation to the other to make them positive, while al-muqabala involved subtracting equal terms from both sides to simplify the equation.

Al-Khwarizmi’s approach was revolutionary because it treated equations as objects that could be manipulated according to specific rules, rather than as geometric relationships that required construction. He provided systematic procedures for solving six standard types of equations, including cases that required completing the square—a technique that would later become fundamental to algebra.

The practical applications of al-Khwarizmi’s methods were extensive. His techniques could be used to solve problems in inheritance, trade, land measurement, and engineering. The systematic nature of his approach made it accessible to a broader audience than the geometric methods of the Greeks, facilitating the spread of mathematical knowledge.

Al-Khwarizmi’s work was not purely theoretical. He recognized the practical importance of his methods and provided numerous examples of their application to real-world problems. This emphasis on practical utility helped establish algebra as a valuable tool for merchants, engineers, and administrators, not just an abstract mathematical discipline.

The translation of al-Khwarizmi’s works into Latin during the 12th century was crucial for the transmission of algebra to medieval Europe. The Latin translation of “The Compendious Book” became the standard mathematical text in European universities for centuries, introducing generations of scholars to algebraic methods.

Al-Khwarizmi also wrote an influential work on Hindu-Arabic numerals, “On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals,” which introduced the decimal positional number system to the Islamic world and later to Europe. This work, translated into Latin as “Algoritmi de numero Indorum,” gave its name to the term “algorithm”—a systematic procedure for solving a problem.

The impact of al-Khwarizmi’s contributions extended far beyond his own time. His systematic approach to problem-solving influenced the development of symbolic mathematics and paved the way for later mathematicians like Omar Khayyam, who solved cubic equations geometrically, and eventually to the fully symbolic algebra of the Renaissance.

The word “algorithm” itself is a testament to al-Khwarizmi’s lasting influence. Medieval Latin writers referred to the decimal number system as “modus algorismi” (the method of al-Khwarizmi), and the term evolved to refer to any systematic computational procedure. Today, algorithms are fundamental to computer science and digital technology.

Al-Khwarizmi’s work also influenced the development of mathematical notation. While he still wrote out equations in words rather than symbols, his systematic approach laid the groundwork for later mathematicians who developed more concise symbolic representations. The transition from rhetorical algebra (expressed in words) to syncopated algebra (using some symbols) to symbolic algebra was a gradual process that al-Khwarizmi helped initiate.

The cultural context of al-Khwarizmi’s work is important for understanding its significance. The Islamic world’s emphasis on practical knowledge and its tradition of synthesizing different intellectual traditions created an environment where innovative approaches to mathematics could flourish. Al-Khwarizmi’s work represents a bridge between the geometric traditions of Greece and the arithmetic traditions of India.

The legacy of al-Khwarizmi’s contributions extends to modern mathematics education. His emphasis on systematic problem-solving and his classification of equation types remain fundamental to algebra instruction. The techniques he developed for “completing and balancing” equations are still taught to students learning algebra today.

In the broader context of mathematical history, al-Khwarizmi’s work represents a crucial transition from the geometric approach of ancient mathematics to the symbolic approach of modern mathematics. His recognition that equations could be manipulated systematically according to specific rules was a conceptual breakthrough that enabled the development of more advanced mathematical techniques.

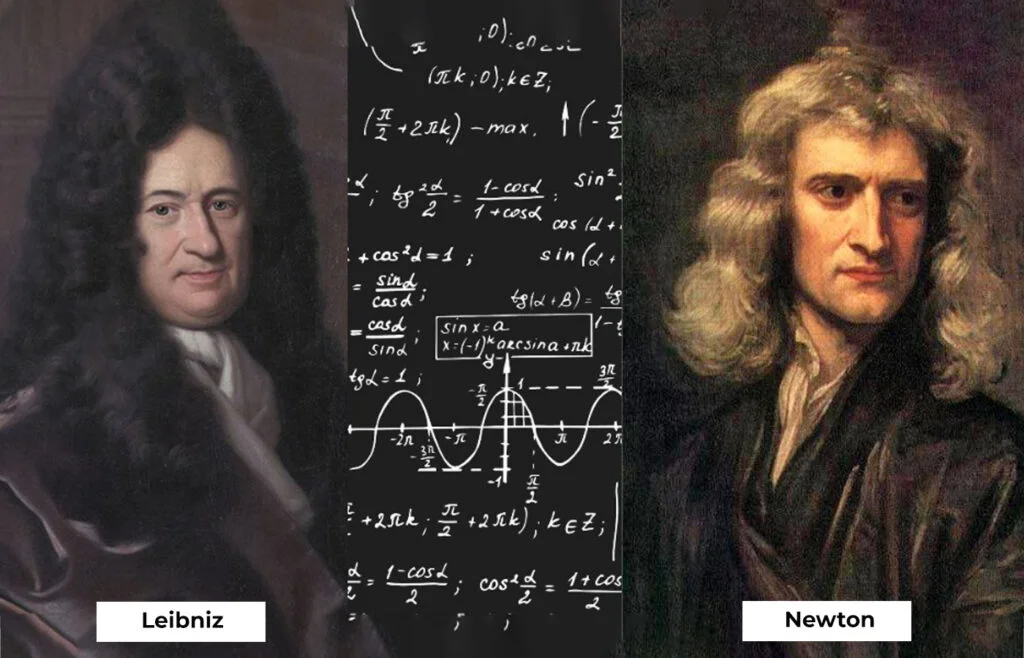

Mechanical Calculators: The Clever Machines of Pascal and Leibniz

The development of mechanical calculators in the 17th century marked a revolutionary advance in computational technology, freeing human calculators from the tedious and error-prone task of performing arithmetic by hand. Two of the most significant early mechanical calculators were invented by Blaise Pascal and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, each addressing different aspects of the computational challenge and demonstrating the potential for machines to augment human mathematical abilities.

Blaise Pascal’s calculator, known as the Pascaline, was invented around 1642 when Pascal was just 18 years old. The device was motivated by Pascal’s desire to help his father, who worked as a tax collector, with the tedious calculations required for his job. The Pascaline could perform addition and subtraction directly and multiplication and division through repeated addition and subtraction.

The Pascaline used a series of interconnected wheels, each representing a decimal digit. As one wheel completed a full rotation, it would advance the next wheel by one-tenth of a rotation, implementing decimal carry automatically. This mechanism, known as a carry mechanism, was one of the Pascaline’s most innovative features and solved a major problem in mechanical calculation.

Pascal’s carry mechanism used a complex system of weights and latches to ensure that carries propagated correctly through multiple digits. When a wheel passed from 9 to 0, a weight would fall and activate a lever that would advance the next wheel. This mechanism was reliable but complex, requiring careful engineering to function properly.

The Pascaline was designed for practical use in business and administration. It could handle numbers up to 999,999 and was particularly useful for addition, which was the most common operation in commercial calculations. Pascal built several versions of the machine and sold a few, but the complexity and cost of manufacturing limited its widespread adoption.

Gottfried Leibniz’s calculator, developed in the 1670s, was a more ambitious machine that could perform all four basic arithmetic operations automatically. Leibniz’s machine, called the Stepped Reckoner, used a novel mechanism based on a stepped drum—a cylinder with teeth of varying lengths that could engage with counting wheels to perform multiplication.

The stepped drum mechanism was Leibniz’s key innovation. By rotating the drum through different amounts, the machine could add a number to itself multiple times, effectively performing multiplication. The same mechanism could be used for division by repeated subtraction. This approach made the Stepped Reckoner much more versatile than the Pascaline.

Leibniz’s machine also featured a movable carriage that could be shifted to change the decimal position of the numbers being operated on. This feature allowed for calculations with decimal fractions and made the machine suitable for more complex mathematical work, including scientific calculations.

The Stepped Reckoner was more complex than the Pascaline and suffered from mechanical reliability issues. The precision required for the stepped drum mechanism was difficult to achieve with 17th-century manufacturing techniques. Despite these problems, Leibniz’s design influenced calculator development for centuries and was used in various forms until the 20th century.

Both Pascal and Leibniz viewed their machines not just as practical tools but as demonstrations of the power of mechanical computation. They believed that machines could perform calculations more reliably than humans and that this reliability was important for scientific and mathematical work where accuracy was crucial.

The philosophical implications of mechanical calculators were significant. They challenged traditional views about the relationship between mind and machine and raised questions about the nature of computation itself. Leibniz, in particular, was interested in the broader implications of mechanized reasoning and believed that many human intellectual activities could be reduced to mechanical processes.

The development of mechanical calculators also reflected the broader intellectual currents of the Scientific Revolution. The emphasis on precision, repeatability, and mechanical explanation that characterized this period found expression in the attempt to mechanize calculation. These machines embodied the scientific ideal of reducing complex processes to simple, reliable mechanisms.

Despite their technical sophistication, early mechanical calculators had limited commercial success. The high cost of manufacturing, the complexity of operation, and the availability of skilled human calculators meant that these machines were primarily curiosities for wealthy patrons and scientific institutions rather than practical tools for everyday use.

The legacy of Pascal and Leibniz’s calculators extended far beyond their immediate impact. Their designs influenced later inventors and established important principles for mechanical computation. The concepts of automatic carry, positional notation, and mechanical multiplication that they pioneered remained fundamental to calculator design until the advent of electronic computers.

The work of Pascal and Leibniz also contributed to the development of mathematical thinking about computation. Their machines demonstrated that complex mathematical operations could be broken down into simple mechanical steps, an insight that would prove crucial for the development of modern computers. The idea that computation could be mechanized became a fundamental principle of computer science.

In the broader context of technological history, the mechanical calculators of Pascal and Leibniz represent an important step in the automation of intellectual work. They showed that machines could perform tasks previously thought to require human intelligence and opened the door to later developments in mechanical and electronic computation.

Conclusion: How Our Tools for Calculation Have Shaped Human History

The journey from ancient counting aids to modern computational algorithms represents one of humanity’s most remarkable intellectual achievements. Each advancement in calculation tools has not only made computation faster and more accurate but has also expanded the scope of problems that humans can tackle, fundamentally shaping the development of science, technology, and society.

The evolution of calculation tools reflects the cumulative nature of human knowledge. Each generation has built upon previous achievements, sometimes making gradual improvements and sometimes achieving revolutionary breakthroughs. The abacus, algebra, mechanical calculators, and electronic computers all represent milestones in this continuous process of innovation and improvement.

Perhaps most importantly, the history of calculation demonstrates the intimate relationship between tools and thinking. As our computational tools have become more powerful, our ability to model complex systems, analyze vast amounts of data, and solve previously intractable problems has expanded dramatically. The development of electronic computers and algorithms has enabled fields like artificial intelligence, genomics, and climate modeling that would have been impossible with earlier computational methods.

The social and cultural dimensions of computational development are also significant. The adoption of new calculation methods has often required changes in education, business practices, and social organization. The transition from Roman numerals to Hindu-Arabic numerals, for example, required widespread educational reform and had profound effects on commerce and mathematics.

The story of calculation also reveals the global nature of mathematical development. Innovations in one culture have consistently influenced and been influenced by developments in others. The transmission of Indian numerals through the Islamic world to Europe, the adoption of Chinese abacus techniques in Japan, and the global spread of electronic computing all demonstrate how mathematical knowledge transcends cultural boundaries.

Today, as we stand on the threshold of quantum computing and artificial intelligence, the lessons of calculation history remain relevant. The fundamental principles of breaking complex problems into simpler steps, using systematic procedures, and leveraging external tools to augment human capabilities continue to guide the development of new computational technologies. Understanding this history helps us appreciate both our achievements and the challenges that lie ahead in the continuing evolution of computational methods.