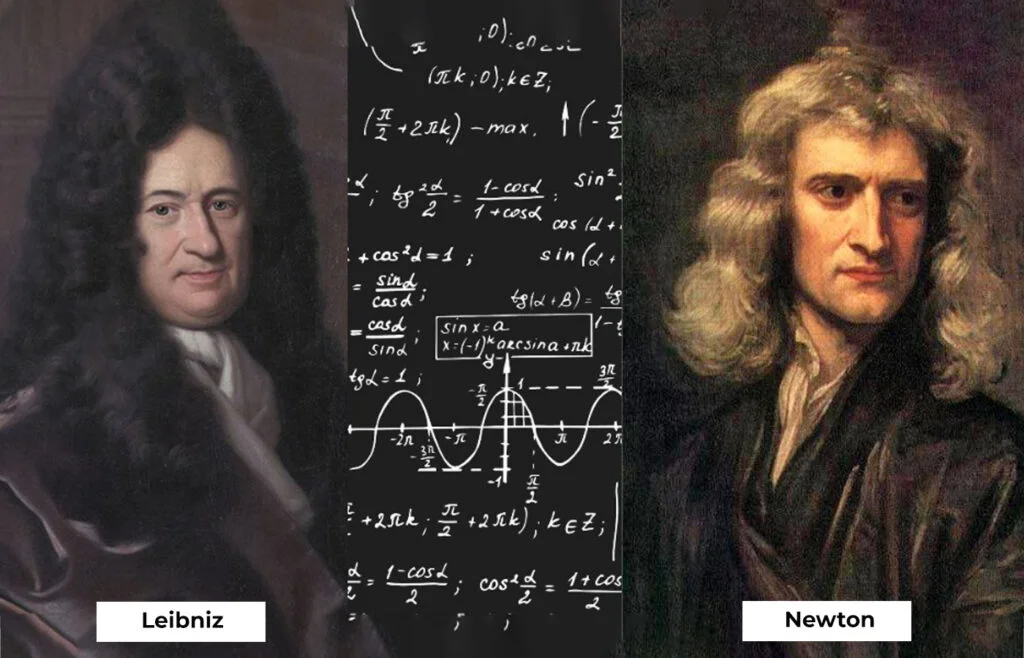

The epic feud between Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz over who invented calculus.

Introduction: The Epic Feud Between Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz Over Who Invented Calculus

The invention of calculus stands as one of the greatest achievements in the history of mathematics, revolutionizing our ability to understand and describe the natural world. However, this monumental breakthrough was accompanied by one of the most bitter and protracted disputes in the history of science: the controversy between Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz over who deserved credit for creating this powerful mathematical tool. This dispute, which divided the mathematical community for generations, reveals as much about human nature and scientific culture as it does about the mathematics itself.

Calculus, the mathematical study of continuous change, emerged from the need to solve problems that classical geometry and algebra could not address. Questions about instantaneous rates of change, areas under curves, and the behavior of moving objects required new mathematical techniques. Both Newton and Leibniz, working independently, developed systematic methods for solving these problems, but their approaches, notations, and philosophical perspectives differed significantly.

The priority dispute was not merely an academic disagreement but a full-scale intellectual war that involved national pride, institutional politics, and personal animosity. The controversy began in the 1670s and continued long after both men had died, with their followers carrying on the feud. The dispute had profound effects on the development of mathematics in Europe, creating a divide between British and continental European mathematicians that lasted for over a century.

What makes this controversy particularly fascinating is that both Newton and Leibniz made genuine and significant contributions to the development of calculus. Newton developed his methods first but published later, while Leibniz published first but may have developed his ideas independently. The question of who invented calculus first is complicated by the fact that both men built on the work of predecessors and that the development of calculus was a gradual process rather than a single moment of inspiration.

The dispute also reflects broader tensions in the scientific culture of the 17th and 18th centuries. Newton, the secretive Englishman who preferred to work in isolation, clashed with Leibniz, the cosmopolitan German who actively corresponded with scholars throughout Europe. Their different approaches to mathematics and science—Newton’s geometric and physical intuition versus Leibniz’s symbolic and philosophical approach—reflected deeper differences in mathematical philosophy.

The resolution of the controversy required historians and mathematicians to examine the development of calculus in detail, leading to a better understanding of how mathematical ideas emerge and evolve. Modern scholarship recognizes that both Newton and Leibniz deserve credit for the invention of calculus, each contributing unique insights and techniques that were essential to the subject’s development.

The Newton-Leibniz controversy also illustrates how scientific priority disputes can both hinder and advance knowledge. While the feud created animosity and division, it also forced mathematicians to examine the foundations of calculus more carefully and to develop more rigorous formulations of its principles. The controversy ultimately contributed to the maturation of mathematical analysis as a rigorous discipline.

Today, both Newton and Leibniz are credited with the invention of calculus, and their respective notations and approaches are recognized as complementary rather than competing. The dy/dx notation of Leibniz and the dot notation of Newton are both used in different contexts, and the modern subject of calculus incorporates insights from both traditions. This recognition reflects a more mature understanding of how mathematical knowledge develops through the contributions of multiple individuals.

The story of calculus also demonstrates the international nature of scientific development. Despite the bitter personal dispute, the mathematical ideas themselves transcended national boundaries and personal animosities. The eventual synthesis of Newtonian and Leibnizian approaches shows how mathematical truth ultimately prevails over personal and national rivalries.

Understanding the Newton-Leibniz controversy provides insight into the human dimensions of mathematical discovery. It shows that mathematics is not created in a vacuum but emerges from the interactions of individuals with specific personalities, cultural backgrounds, and intellectual traditions. The controversy reminds us that behind every mathematical theorem and every scientific law are human beings with all their strengths, weaknesses, and foibles.

The Problems They Faced: What Questions Led to the Need for Calculus?

The development of calculus was driven by a set of fundamental problems that had puzzled mathematicians and natural philosophers for centuries. These problems could not be solved using the mathematical techniques available in the 17th century and required entirely new approaches that would eventually become the foundation of mathematical analysis. Understanding these motivating problems helps explain why calculus was such a revolutionary development and why it was discovered independently by multiple mathematicians.

One of the central problems was determining instantaneous rates of change. Classical mathematics could calculate average rates of change over intervals, but determining the speed of a moving object at a specific moment or the slope of a curve at a specific point required a new concept. This problem arose naturally in the study of motion, where understanding instantaneous velocity was crucial for describing the behavior of falling objects, projectiles, and planetary motion.

The problem of finding tangents to curves was closely related to the question of instantaneous rates of change. Given a curve, mathematicians wanted to find the line that just touches the curve at a specific point, representing the direction of the curve at that point. This problem had applications in optics, where the angle of reflection depends on the tangent to a mirror’s surface, and in mechanics, where the direction of motion depends on the tangent to the path of motion.

Calculating areas under curves presented another major challenge. While the areas of simple geometric shapes like rectangles, triangles, and circles were well understood, finding the area under more complex curves required new techniques. This problem, known as quadrature, had practical applications in determining volumes of irregular solids, calculating work done by variable forces, and solving problems in probability theory.

The problem of maxima and minima—finding the highest and lowest values of functions—was important for optimization problems in geometry, physics, and engineering. Determining the shape of a container that holds the maximum volume for a given surface area, or finding the path that minimizes travel time, required techniques for identifying points where functions reach their extreme values.

Related to these geometric problems were questions about the lengths of curves and the areas of curved surfaces. Calculating the circumference of an ellipse, the surface area of a sphere, or the length of a parabolic arc required methods that went beyond classical geometry. These problems had practical applications in navigation, astronomy, and engineering.

In physics, the study of motion under variable forces created new mathematical challenges. Galileo’s work on uniformly accelerated motion had shown how to describe motion with constant acceleration, but understanding motion under forces like gravity or spring forces that vary with position required more sophisticated mathematical tools. Newton’s laws of motion, formulated in terms of rates of change, made the development of calculus essential for mathematical physics.

Astronomical problems also drove the need for calculus. Kepler’s laws of planetary motion described elliptical orbits, but calculating the position of a planet at a given time required solving what became known as Kepler’s equation—an equation that could not be solved using algebraic methods. The complex motions of planets, moons, and comets required mathematical techniques for analyzing continuous change.

The problem of finding the sum of infinite series arose in attempts to calculate areas and volumes using the method of exhaustion, a technique used by ancient Greek mathematicians. While this method could prove that certain sums had specific values, it provided no systematic way to discover those values. The development of calculus provided tools for summing infinite series and for understanding the convergence of such sums.

Optics presented geometric problems that required new mathematical methods. The design of lenses and mirrors to focus light involved finding curves with specific properties, and the analysis of how light rays behave when reflected or refracted required understanding the geometry of curved surfaces. These problems had practical applications in the construction of telescopes, microscopes, and other optical instruments.

Probability theory, in its early development, created problems involving areas under curves that represented probability distributions. The problem of dividing stakes fairly in an interrupted game of chance, solved by Fermat and Pascal, involved summing infinite series. More complex probability problems required techniques for calculating areas and volumes that classical mathematics could not provide.

The inverse tangent problem—given information about the slope of a curve at each point, find the curve itself—was particularly important for solving differential equations. This problem arose naturally in physics when trying to determine the path of an object from knowledge of the forces acting on it. The development of techniques for solving such problems became a central concern of calculus.

These problems were not isolated curiosities but represented fundamental challenges to mathematical understanding. They required mathematicians to think about infinity, continuity, and limits in new ways. The solutions to these problems would not only advance mathematics but would also provide the tools necessary for the scientific revolution in physics and astronomy.

The fact that these problems arose in multiple contexts—geometry, physics, astronomy, and engineering—explains why calculus was discovered independently by several mathematicians. The need for new mathematical techniques was so pressing and so widespread that it was almost inevitable that someone would develop systematic methods for addressing these challenges. The specific form that calculus took reflected the particular interests and approaches of its creators, but the fundamental insights were driven by the shared recognition that new mathematical tools were essential.

Newton’s Approach: His Method of “Fluxions” to Describe Motion and Physics

Isaac Newton’s development of calculus, which he called the “method of fluxions,” was deeply rooted in his work on physics and his desire to describe mathematically the motion of objects and the forces acting upon them. Newton’s approach was geometric and physical, emphasizing the intuitive understanding of motion and change rather than symbolic manipulation. His method reflected his broader philosophical approach to mathematics and science, which sought to ground abstract concepts in concrete physical reality.

Newton began developing his method of fluxions in the 1660s, during his annus mirabilis (miraculous year) when he made his fundamental discoveries about gravity, optics, and calculus. Working largely in isolation at his family home in Woolsthorpe during the Great Plague of London, Newton developed the mathematical tools he needed to describe his physical theories. His approach was driven by his desire to understand the physical world rather than by abstract mathematical curiosity.

In Newton’s system, variables were thought of as continuously flowing quantities, which he called “fluents.” The rate of change of a fluent was called its “fluxion,” represented by a dot over the variable (thus, the fluxion of x was denoted x̄). This notation reflected Newton’s physical intuition about motion, where quantities change continuously over time. For example, if x represents the position of a moving object, then x̄ represents its velocity.

Newton’s fundamental insight was that differentiation (finding fluxions) and integration (finding fluents from fluxions) are inverse operations. This relationship, now known as the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, was central to Newton’s approach. He recognized that to find the area under a curve, he needed to find a function whose fluxion (derivative) is the given function. Similarly, to find the fluxion of a function that represents area, he would obtain the original function that defines the curve.

Newton’s method was particularly well-suited for solving problems in physics. To analyze the motion of a planet under gravitational force, Newton would consider the position of the planet as a fluent, its velocity as the fluxion of position, and its acceleration as the fluxion of velocity. By setting up equations relating these quantities, he could derive the laws of planetary motion and calculate specific orbits.

One of Newton’s key techniques was the use of infinite series to represent functions. He developed methods for expanding functions in power series, which allowed him to perform differentiation and integration term by term. This approach was particularly useful for functions that could not be expressed in closed form, such as the integral of certain algebraic functions. Newton’s work with infinite series showed how calculus could handle a much broader class of functions than classical mathematics.

Newton’s approach to calculus was geometric as well as algebraic. He often used geometric constructions to understand and solve calculus problems, drawing on the classical Greek tradition of geometry. For example, he would analyze the motion of a point along a curve by considering the tangent to the curve at each point, relating the geometric concept of tangency to the physical concept of instantaneous velocity.

The application of Newton’s fluxional method to physics was most clearly demonstrated in his “Principia Mathematica” (1687), where he used calculus to derive his laws of motion and universal gravitation. In the Principia, Newton showed how to calculate the orbits of planets, the motion of comets, the tides, and the precession of the equinoxes. These calculations required sophisticated techniques of differentiation and integration that were only possible with the tools of calculus.

Newton’s notation for calculus, based on dots for fluxions and his method of prime notation for higher derivatives, was designed to emphasize the physical interpretation of mathematical operations. The fluxion of x (x̄) represented velocity, the fluxion of the fluxion (ẍ) represented acceleration, and so on. This notation made it easy to translate between mathematical expressions and physical concepts.

Despite developing his method in the 1660s, Newton was reluctant to publish his work on calculus. He was concerned about criticism and controversy, and he preferred to develop his ideas thoroughly before sharing them. This reticence meant that his work on calculus was not widely known until much later, allowing Leibniz to develop and publish his independent version of calculus first.

Newton’s approach to calculus reflected his broader philosophical outlook on mathematics and science. He believed that mathematical concepts should be grounded in physical reality and that abstract mathematical reasoning should be connected to concrete phenomena. This perspective influenced his preference for geometric methods and his emphasis on the physical interpretation of mathematical operations.

Newton’s method of fluxions also reflected the mathematical traditions of his time. He built on the work of earlier mathematicians like Fermat, who had developed methods for finding maxima and minima and tangents to curves, and Wallis, who had worked with infinite series. Newton synthesized these earlier approaches into a comprehensive system that could handle a wide range of problems in mathematics and physics.

The power of Newton’s approach became apparent in his ability to solve problems that had defeated earlier mathematicians. His calculation of the speed of sound, his analysis of the shape of a rotating fluid, and his derivation of the laws of motion from his inverse square law of gravitation all required sophisticated calculus techniques. These successes demonstrated the practical value of his method and justified his confidence in its power.

Leibniz’s Approach: His Superior Notation (dy/dx and ∫) That We Still Use Today

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s approach to calculus was fundamentally different from Newton’s in both philosophy and implementation. While Newton developed calculus as a tool for physics, Leibniz viewed it as a universal symbolic language for reasoning about change and continuity. His approach was more algebraic and formal, emphasizing the manipulation of symbols according to precise rules. Most significantly, Leibniz developed a notation system that was so elegant and powerful that it became the standard for calculus and is still used today.

Leibniz began working on calculus independently in the 1670s, several years after Newton had developed his method of fluxions. Unlike Newton, who worked in relative isolation, Leibniz was part of a broader European intellectual community and corresponded with many mathematicians. His approach was influenced by his work on logic and his belief that mathematics could be systematized through the development of appropriate symbolic languages.

Leibniz’s notation for calculus was revolutionary in its clarity and expressiveness. He introduced the symbol d for differentials, writing dy/dx for the derivative of y with respect to x. This notation made the geometric meaning of the derivative as a ratio of infinitesimal changes intuitively clear. The integral sign ∫, which Leibniz derived from the long S in “summa” (Latin for sum), represented the process of summation that is inverse to differentiation.

The power of Leibniz’s notation became apparent in its ability to express complex relationships simply and clearly. The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, which relates differentiation and integration, takes the elegant form ∫(dy/dx)dx = y + C in Leibniz’s notation. The chain rule for differentiation, d/dx[f(g(x))] = f'(g(x))g'(x), is expressed naturally in Leibniz’s system. This notational clarity made calculus much easier to learn and apply than it had been with earlier methods.

Leibniz’s concept of differentials was central to his approach. He thought of dx and dy as infinitesimally small quantities, representing infinitely small changes in x and y. While this concept was intuitively appealing, it was also mathematically problematic, as the notion of infinitesimals would not be rigorously defined until the 19th century. Nevertheless, Leibniz’s intuitive use of infinitesimals led to correct results and made calculus accessible to a broader audience.

Leibniz’s approach was more algorithmic than Newton’s. He developed systematic rules for differentiation and integration that could be applied to a wide variety of functions. His rules for differentiating products (the product rule), quotients (the quotient rule), and composite functions (the chain rule) provided a comprehensive toolkit for calculus calculations. These rules, expressed in his clear notation, made calculus a practical tool for solving problems.

Leibniz published his work on calculus much earlier than Newton, beginning with a short paper in the Acta Eruditorum in 1684. This publication described his differential calculus and included examples of its application. A paper on integral calculus followed in 1686. Leibniz’s willingness to publish his ideas made them available to the broader mathematical community and established his priority in the eyes of many scholars.

Leibniz’s philosophical approach to mathematics influenced his development of calculus. He believed that a perfect mathematical notation would make reasoning as mechanical as calculation, reducing the need for creative insight. His notation for calculus reflected this belief, providing a systematic way to perform mathematical operations. This vision of mathematics as a universal language for reasoning influenced the development of symbolic logic and computer science centuries later.

The superiority of Leibniz’s notation became apparent in its flexibility and generality. His notation could easily be extended to functions of several variables, where partial derivatives like ∂z/∂x and ∂z/∂y clearly indicated which variable was being differentiated. The notation also made it easy to express higher-order derivatives and to work with differential equations.

Leibniz’s approach to calculus was influenced by his study of Pascal’s work on the arithmetic triangle and his interest in summing series. He recognized that integration could be viewed as the summation of infinitesimal quantities, which led to his integral notation. This perspective connected calculus to earlier work in the theory of infinite series and provided a unifying framework for understanding mathematical analysis.

Leibniz’s notation also facilitated the development of new areas of mathematics. The clear distinction between dependent and independent variables in his notation made it easier to develop the theory of functions. His approach to differentials suggested generalizations to multiple variables and laid the groundwork for the development of differential geometry.

The controversy with Newton arose partly because Leibniz’s notation made calculus more accessible and attractive to other mathematicians. Continental European mathematicians quickly adopted Leibniz’s approach, while British mathematicians, loyal to Newton, continued to use fluxional notation. This division hindered communication between mathematicians and slowed the development of calculus in Britain for nearly a century.

Leibniz’s emphasis on notation and formal rules, while initially criticized as lacking rigor, proved to be prophetic. Modern mathematics has shown that careful attention to notation and formal systems can lead to deep insights. Leibniz’s vision of mathematics as a symbolic language has been realized in areas like computer algebra and automated theorem proving, where mathematical reasoning is reduced to symbolic manipulation.

The enduring success of Leibniz’s notation demonstrates the importance of good mathematical notation in the development of mathematical ideas. His symbols dy/dx and ∫ have survived for over three centuries not just because they were first, but because they express mathematical concepts with exceptional clarity and precision. This notation has enabled countless mathematicians and scientists to understand and apply calculus effectively.

Conclusion: Why Both Men Are Now Credited and How Their Work Changed Science Forever

The controversy between Newton and Leibniz over the invention of calculus, while bitter and protracted, ultimately led to a richer understanding of both the mathematics and the history of its development. Modern scholarship recognizes that both men made genuine and significant contributions to the creation of calculus, each bringing unique insights and approaches that were essential to the subject’s development. Newton’s physical intuition and geometric approach provided the foundation for applying calculus to mechanics and astronomy, while Leibniz’s formal notation and algebraic methods made calculus accessible and powerful as a general mathematical tool.

The recognition that both Newton and Leibniz deserve credit for the invention of calculus reflects a more mature understanding of how mathematical knowledge develops. Mathematics is not created by isolated individuals working in vacuum, but emerges from the interactions of many minds building on previous work and approaching problems from different perspectives. The development of calculus was inevitable once the motivating problems became pressing enough, and it was almost certain that multiple mathematicians would contribute to its creation.

The work of both Newton and Leibniz changed science forever by providing the mathematical tools necessary for the quantitative description of natural phenomena. Newton’s application of calculus to physics enabled him to formulate his laws of motion and universal gravitation, laying the foundation for classical mechanics. The ability to describe motion, forces, and energy mathematically transformed physics from a qualitative science into a quantitative one, enabling precise predictions and technological applications.

Leibniz’s notation and formal approach made calculus accessible to a broader community of mathematicians and scientists. The clarity of his symbols facilitated the spread of calculus throughout Europe and enabled mathematicians to push the subject to new heights. The development of mathematical analysis in the 18th and 19th centuries, leading to the theories of functions, differential equations, and complex analysis, was made possible by the solid foundation that Leibniz’s notation provided.

The Newton-Leibniz controversy also had important consequences for the development of mathematical culture. It highlighted the need for clear communication and priority standards in scientific work. The eventual resolution of the dispute, recognizing both men’s contributions, established a precedent for sharing credit in cases of simultaneous discovery. This recognition has influenced how the scientific community handles priority disputes in subsequent centuries.

Most importantly, the invention of calculus opened up entirely new domains of mathematical and scientific inquiry. The ability to handle continuous change mathematically enabled the development of fields like fluid dynamics, elasticity theory, electromagnetism, and quantum mechanics. Without calculus, the mathematical description of these phenomena would have been impossible, and the technological advances they enabled would not have occurred.